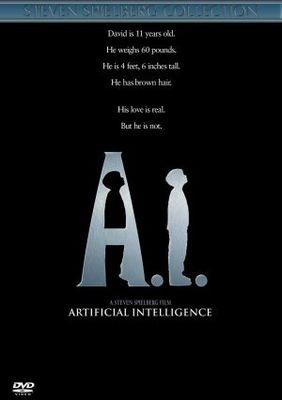

A.I. Artificial Intelligence: The creation of dreams

Spielberg has very blatantly lied before - ie taking credit for the more absurd and criticized aspects of Crystal Skull even though Lucas had already admitted they were his ideas - but there's no reason to believe that he was pulling our leg (or even exaggerating) with attributing the supposed sentimentality of AI's ending to Kubrick, and even in terms of mere concept alone the ending - with its advanced robots 2000 years in the future discovering the last robot to have ever had human contact. People tend to forget that Kubrick is a distinctly situational filmmaker, something more common towards more blatantly humorous directors, and is generally content to absolve drama for merely exploring the dynamics of what exactly happens within a given circumstance of a usually exceptional kind. While this tonal jump is unexpected and takes a little bit of getting used to, its completely in line with the rest of the film - robots who now speak their own language, look nothing like humans and have developed an entirely new form of communication look on as the last robot based on a human watches their "dreams" collapse, as though expressly seeing the limitation of being based on a human at all.

I always think about Spielberg talking about his friendship with Kubrick, and how he designated 2001 as "not science-fiction, but more like science-eventuality," and AI is very obviously, at least near its final moments, Spielberg's interpretation of Kubrick's prognosis of what might happen when human life inevitably goes extinct. The films strengths however, aren't necessarily Kubrick's as much as their obviously Spielberg's, because Spielberg is probably the master of filmmaking in the subjective style in ways that Kubrick was never really able to match - so of course he would hand the project off to him. Kubrick could never direct a film about a robot who could be programmed to have the same passions, desires and feelings of a human being. The only person who ever could would have to be the director of ET. Because Kubrick wouldn't be able to stop himself from remaining distanced, detached, godlike. Spielberg would instinctively empathize with the robot, thus proving Kubrick's point all along. And as such, the first chunk of the movie is flatly astonishing filmmaking on any level, with David introduced to us in an alienating manner from the perspective of the "parents," to gradually shift perspective by slowly navigating from the "parents" subjectivity to David's, so that by the point of his abandonment, we don't just empathize with him, but we identify with him. Not even Hitchcock at his best could ever come close. This comes in part by Spielberg's shot selection and subtle montage - possibly at the absolute height of his ability - focusing not on any specifically dramatic moments but David's mere perception of and reaction towards basic phenomena, the way a child would upon seeing something for the first time, or the way a robot would when learning that reaction the same way a human does, or the way that the viewer of a film would react from image to image as a film plays.

It would be helpful to write on AI with a visual accompaniment because of how much information the film imparts on us throughout with both the speculative circumstances of Kubrick's situational approach and the broader thematic outliers from Spielberg's emotional one happening pretty much at the same time. Yet it works, because we can perceive the limited expanse of emotions themselves while being allowed to experience those emotions with the character, which is utterly remarkable. AI's brilliance is that it's a grand synthesis of these two filmmakers approaches, though ironically they're not significantly different regarding their thematic interests. AI becomes about the limits of human emotion and the capacity of human idealism, and that artificial intelligence may not just surpass humanity in terms of intelligence, but in empathy and love as well. At the same time, we can see how easily these things can be created and manipulated, like the ease of which the mother character gradually becomes attached to David. Of course there's no reason why she shouldn't - David has every characteristic of a "real" child and the closest thing to that relationship would be no different than a child raised from adoption. But he's nevertheless increasingly treated as an outsider before being cast outside of the family unit entirely - Spielberg's sensitivity towards outsider figures (both those of supposed minority status and not) goes unusually unremarked upon within studies of his work, that Kubrick would pass the film off to him seems pretty natural. But it's Spielberg's triumph first and foremost because it also identifies the traditional family unit as a source of trauma itself. It's something that's blatant in all his movies dealing with family, but never clearer than here.

Fernández y Milanese

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario